|

Contrasting to some of my previous posts showcasing practices of more developed countries like Japan and Sweden it is important to reflect upon how accessibility is considered in places that are not so wealthy in financial means to build more accessible spaces. This past November I had the fortune to travel around Cuba, visiting towns and cities of all sizes. What caught my eye in particular is the vibrant sense of community and cooperation everywhere I visited.

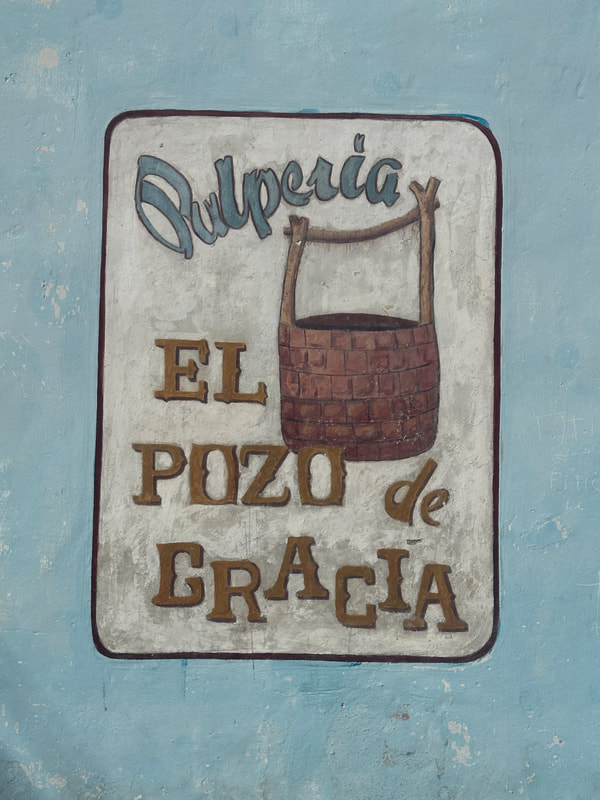

Cuban people are passionate, and this reflects in their culture, with a society that remains connected and a sense of community support systems that feel alive. People socialize on the streets, support and play with their neighbours and genuinely look out for each other. Streets feel safe by day and night. This social capital is something many western countries have lost. By contrast Cuba struggles with crumbling infrastructure due to lack of repair, replacement, or expansion. This is due to a variety of factors with the ongoing embargoes restricting access to materials and hard currencies and a sense of limited government organizing capacity. Still the desire by the people for a better, prosperous society and nation is clear! This duality of high social capital yet low economic capital requires a different approach to considering accessibility. Increasing accessibility is typically tied to high quality infrastructure including the retrofitting of older features or integration of best practices with new development informed by codes, standards, and regulations. However, what does that look like when funds to upgrade or replace physical infrastructure are unavailable and even basic services struggle with under-investment or neglect? People with low vision and blindness do navigate the streets and communities of Cuba. They are actively out and about despite little to no application of accessibility features to the streetscape and buildings. In fact, there are more obstacles for them to navigate with roadside ditches, limited traffic controlled crossings and almost every manner of transportation using the roadways. Some features such as textured paths are evident but very inconsistent in their application. Housing is provided and where possible within the constrained resources of society; creative, yet inconsistent accommodations are made to infrastructure. People with special needs or requiring accommodations remain within their communities, not institutions. Homelessness is also a rare sight in Cuba. Despite economic constraints there seems to remain a social commitment that all Cubans have access to housing and food, if only at a basic level. This cannot be said for many western societies even with social support programs. The insight from Cuba is that accessibility is the combination of social systems and the built environment. Individuals, communities, and government services play at least an equal role to increasing accessibility alongside changes to the way we design our communities.

0 Comments

In my advocacy for the design of more visually accessible cities I am often asked who is the leader? What are the best practices and who is getting it right? While I have yet to find a city or country that has it all figured out Japan is the closest to putting together the pieces. Last month I had the fortune to visit this bustling and culturally rich country, visiting several cities that offered a good sampling of how they approach accessible design and in particular visual accessibility. For context Japan is a very populous country of roughly 126 million people confined on a series of connected islands. Combined, that substantial population and limited land are two factors that typically set the foundation for more accessible cities. The country is fundamentally built around public transportation having opted nationally to avoid mobility oriented around cars and planes in the early 1960s. Add in two other key factors unique to Japan, an older demographic and a culture based on respect and the advanced practice I saw is further appreciated. In terms of demographics Japan’s largest population cohort is amongst seniors around 75 years in age meaning they have a large portion of the population needing assistance with mobility beyond those who may have a non-age related mobility restriction. The next population bulge at 55 years will soon add to age related mobility limitations. Surrounding all of this is Japanese culture which emphasizes respect and honouring others. This means accommodating others is part of the culture as is respect for the public realm. The result: crime, vandalism and litter are rare. Thus the public realm always appears clean, orderly and well maintained even before any specific accessible design features. It is not perfect of course as changes to infrastructure and cultural mindsets about disabilities takes time. The big push toward more accessibility started in 2006 when Japan passed the Barrier Free Act requiring public then private entities to improve access. This effort with later propelled by the 2020 Tokyo Olympic games with the adoption of the Universal Design 2020 Action Plan in early 2017. Now in terms of what specifically makes Japan a unique leader. Accessible design is comprehensive and consistent. Over the course of several days I observed a very comprehensive application of accessible design features around Tokyo. First I thought it was just Tokyo that had it figured out. Then I visited Kanazawa, Takayama, Hiroshima and Kyoto only to pleasantly find that they too applied the same practices on an equally comprehensive basis. From tactile walking surface indicators to frequent and easy to read signage, the form and application was continuous and thorough. Attention and guidance walking surface indicators are evident both indoors and out using a consistent yellow or dark grey colour and are contiguous even when crossing streets. In some instances the amount of yellow on the ground from walking surface indicators was a bit overwhelming so there are some aesthetic choices and challenges to be considered. My sense however is that these also provide navigation guidance for the fully sighted as they make paths of travel clear and thus avoid congestion. Signage consistently used large font, contrasting colours and was more often located at eye level. This is also true for digital terminals such as ticketing machines, bank machines and electronic information boards. Moving from one facility such as a public train station to a private shopping centre didn’t result in forms, colours and styles changing drastically. This reflects Japan having set some common design standards for both public and private facilities. All the senses and surfaces are engaged.

Information is also provided in tactile form through the use of Braille. Note that this is Japanese braille so may not be familiar to visitors. Hand rails are also standard wherever elevation changes allowing for increased stability for movement. All surfaces including floors and walls are also put to work. Arrows on the ground communicate everything from directions of travel for crowd management to directions toward popular destinations. Full painted lines are also common allowing a person to follow it all the way to their destination. Mobility is a way of life, that means wayfinding and data. In a country that is densely populated and oriented around public transportation getting around quickly and easily is critical. Detailed information has been integrated into apps like Google Maps and Waze easing movement through complex transportation systems guiding you to the right levels, platforms and even best train carriages based on connections and capacity. At the same time real-time information on departures and arrivals at train stations and bus terminals is in large font and high contrasting colours. Audible announcements on destinations and stops can also be heard at nearly every station or on-board vehicles. Announcements are provided in Japanese and English. Combine these elements with frequent, larger and well-designed wayfinding maps and the complexity of Japan’s large cities becomes significantly more manageable. I would like to say this is a hopeful and optimistic post about how bold investments are being made in new or renewed options to move people between communities of all sizes however it is more a call out to the prolonged under-investment and deterioration of those options. It seems Canada is finally hitting rock bottom on the state of inter-city transportation options beyond the private automobile. This really jumped out at me again when reading this CBC article about a BBC reality show attempting a race across British Columbia on public transit. They struggled, and in one of the more well-connected provinces. As someone who cannot drive I have lived the experience of navigating a country mostly preoccupied with investments in personal automobile travel. Intercity connections by transit have deteriorated, encouraged by the automobile industry and paralysis of government studies; accelerated by the impacts of the COVID pandemic. Options are often infrequent or expensive while their users are less likely to afford high transportation costs. Prior to the pandemic many inter-city transportation options were at the tipping point. Evidenced with the rapid exit of Greyhound bus services within two months of the pandemic’s onset. Today some new companies are popping up to fill portions of the vacated routes however those leave out many communities. Further, they often no longer use bus terminals, instead stopping on the sides of roads or back end of buildings making for a less welcoming, safe and accessible experience. By contrast many new airlines have hit the skies who are on one hand driving down prices while driving up greenhouse gas emissions illustrating the distorted economics that influences both accessibility and climate change. Rail travel has also struggled due aging rail infrastructure, prolonged studies and diminishing services. Services of VIA rail Canada on Vancouver Island halted over ten years ago while studies continue while services in northern Manitoba nearly ended after an eighteen month pause due to storm damage to tracks. Meanwhile growing communities are calling for improved services to provide alternatives, aligned with Canada’s climate change commitments. A case no more evident than that from the City of Belleville and other communities requesting restoration of commuter rail services, denied due to a lack of trains. Now I appreciate that much of those train cars left over from Pacific National and Canadian National services have passed their service life; however, Canada builds trains!

When planning a recent trip to visit family I was shocked at the distorted economics of travel. In 1998 I bought a return plane ticket Toronto to Vancouver for $500. Today, that same ticket can be purchased for $158. A return train ticket on VIA rail from Toronto to Belleville to complete the trip would run me around $130. Other countries are reinventing their inter-city transportation systems to support accessibility, climate goals and more transportation alternatives. Spain and Portugal have radically reinvented their once obsolete passenger rail system while France has even banned domestic commercial flights of under two hours in favour of rail travel. Think of how many flights that could take out of the air between Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa alone alongside Calgary and Edmonton. Completed by well organized bus and train services with modern stations would further increase accessibility and hopefully reduce passenger frustration at airports.

We cannot just electrify private automobiles to meet climate and sustainability goals. We must give active, priority investment to the alternatives. Mobility is one area where the equity dimension of climate change and accessibility truly intersect. Otherwise, our cities will continue to be chocked by traffic and our smaller communities continue to become more inaccessible to people without the means, ability or interest to drive. Let's consider an equitable investment in sustainable transportation infrastructure. City streets, sidewalks and pathways are becoming a bit more crowded these days. With the growing availability and variety of electric mobility options there are more people competing for the same space to get around. How we move about cities is changing rapidly not only technology but also rapidly shifting work patterns. At the same time regulation is lagging to keep up in managing the use of different mobility options leaving sometimes conflicting understandings of what can be used where and who has the right of way? Here we will dive into the rapidly growing use of a variety of electric mobility vehicles beyond the automobile and typical transit systems. First off there are many forms of scooters and electric or e-mobility devices. From e-bikes, electric standing scooters to riding scooters that can sometimes more resemble small motorbikes and now electric unicycles. Some of these options can move at speeds up to 60km per hour! Crash helmets sold separately. Rules for each vary by the type of vehicle and the jurisdiction where it is used. Some are permitted to use sidewalk spaces while other are limited to road use only. Others are not yet be approved for use but uptake is ahead of government approval. Many municipalities are stuggling with questions of regulation such as in the City of Fredericton. How would bylaw officers chase after an electric unicycle? This growing variety of uses, undefined or unacknowledged rules of where they can travel can create particular challenges to accessibility. First, for the pedestrian on the street who may feel unaware of these other mobility devices. They may feel threatened by sharing spaces with high-speed vehicles moving in unpredictable ways within pedestrian space. Will the person on the electric mobility vehicle have enough time or mindfulness to avoid the person with a white cane, walker or stroller? Even when unattended obstacles may be created by these vehicles being left in inappropriate places.

Second the ability of people with accessibility needs to access these forms of mobility for their own use. Some of these vehicles are available on the market and thus available to anyone for purchase. Others are part of sharing systems supported by municipalities such as they City of Calgary, local non-profits or private business. Sharing systems are typically accessed through application based systems on person mobile devices so those apps need to be up to current accessibility standards with features live dictation, voice control and high contrast options. Use of these devices in low traffic areas would further accommodate people who want to participate but may be uncomfortable on busy streets. This later point of course is a tricky balance between creating safe spaces for the electric vehicle user, pedestrians and other uses. There are a variety of options to help improve the experience and safety of all users that city planners, regulators and community activists can promote:

Caption - Street scene in Malmo of pedestrians and cyclists navigating a traffic circle before a street of traffic with a local farmers market in the background. A multitude of users navigating shared space creating a diverse urban space full of activity. Recently I had the fortune to visit the forward-thinking city of Malmo, Sweden. I had heard many stories about Malmo through colleagues, planning journals and one of their former mayors who spoke at a conference here in Canada many years ago. Malmo is known for being one of the most cycle, transit and active mobility friendly cities in the world. It also happens be just across the strait, or only fifteen minutes by frequent train from Copenhagen, Denmark who holds a similarly well-deserved reputation. Malmo is the second largest city in Sweden with a core population of 344,000 people that is growing quickly. Founded in 1275, this is a city that has seen and continues to live through many transformations. From its old world city centre, two distinct eras of industrial waterfront development, new and modern styled shore development and a fairly young population the city blends a diverse variety of neighbourhoods and eras of infrastructure. Thus, consistency in accessibility features is one of their main challenges in accommodating visitors and locals alike. In all my travels I have yet to uncover a place that has mastered accessibility, designing all their public spaces in ways that are consistent in their wayfinding, design features and accommodations to meet the needs of diverse users. So with that context in mind I enjoyed discovering Malmo, observing and learning what was working well and where progress could be made. The accessibility of space and desire to create inclusive environments is evident however with room for improvements. Overall Malmo has made deliberate efforts to balance investments in infrastructure and services to help people move by transit, bike, scooter and foot. E-scooters have become commonplace in the city over the past five years and like in my other cities around the world are the latest user and competitor for space on the street. That said there does seem to be an odd hierarchy given to users. Cyclists and scooters tend to be given priority in all spaces above vehicles and pedestrians. This leaves pedestrians, and those with mobility limitations in a much more vulnerable space. There is a strange norm that a senior with a walker, mother with a stroller or person with a cane gives way to a cyclist. Staff from the city advised there is a dedicated role supporting coordination of cycling infrastructure and even another for skateboarders however nobody dedicated to pedestrians, the most vulnerable user. After having some time to observe all these users dance through the streets, I was struck by the more mellow pace everyone moved at compared to North America. There is a collective consciousness among all the users; drivers, walkers, cyclists, scooterists that others are moving around them and to be patient. This is a key cultural factor for why everyone seems to stay safe and overall be less stressed. While having separated infrastructure for cyclists and pedestrians helps with the safety aspect creating a cultural norm of shared, respected space is a far greater success factor in establishing accessibility. A few specifics of good practice worked and where gaps existed for improvement:

Travel and tourism is a powerful way to break down barriers, learn about different cultures, make new friends and challenge conceptions. Humans have an innate curiosity about our surroundings near and far. A tourist may be exploring a far away country home to a very different culture or another city only an hour away from home. Sometimes we can even be a tourist in our own city when trying something new or welcoming visitors. Imagine you are a visitor to a new country, city or place away from home. What challenges are you likely to face? Language, culture, currency, different laws or norms, people who may look or act differently than you. These are all daunting things to absorb. If you travel often to new places this adjustment can become more commonplace however even veteran travellers face culture shock, stress and various other challenges. Now imagine that you also face some form of physical, mental or psychological barrier. This may add an overwhelming or even impossible layer to you visiting a new place, aside from your adjustments upon arrival. Preparing for your trip may require much more planning and attention to detail. Thinking about how you will get around, your path of travel, what infrastructure and human support services may be in place or available on request. Increasingly tourism agencies are more aware of accessibility needs and able to provide in formation. Public and private buildings are making information on accessibility for their spaces available online or by phone. Wayfinding apps can also be useful in navigating public streets and public transportation. Conversely, being willing to travel will also need to come with a high level of comfort to adapt and figure things out on the go knowing that accessibility details may not be available beforehand. This will often need to include a willingness to ask for assistance, a task that is often not easy to do as it involves communicating personal challenges and vulnerabilities. Cultural sensitivity toward “disability” is also highly varied around the world. As a tourist you are already in an unfamiliar place. Your surroundings will constantly be changing and new to you. From crossing borders, to navigating airports or checking-in to new accommodations. Even if you have visited a place previously, memory fades and recognition of landmarks, streets and destinations will remain challenging. You may be traveling with someone and thus have support available, even if on a limited basis as you need. Alternatively you may be solo, planning or navigating on your own. Both are rewarding experiences. However you travel and wherever you choose to go know that it will be different from home and you are welcome to be there. People with physical, mental or emotional limitations have equal rights to travel as those who are barrier free. Right and reality however do not always align. Many cities around the world are working hard to make improvements to the infrastructure, wayfinding systems and social services to improve accessibility for all. These efforts are not entirely uniform and I have yet to find a city that has really nailed visual and physical accessibility in a persistent and systematic way. If you have a passion for travel, big or small, or know someone or faces obstacles to exploring their dreams here are some techniques you can consider:

If you are a city planner, municipal leader, community advocate or other person looking to improve accessibility for visitors to your community here are some techniques you can consider:

Writing this in July of 2021 it has been just over the past sixteen months since our ways of living, working and socializing were transformed in March 2020. Following three progressively intense ways of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada the future is now starting to look brighter. Vaccines are rolling out rapidly here in Canada, people are eagerly lining up for their shots and health restrictions are easing in informed ways in most places. People are starting to make life plans again, businesses reopening and the long-lost hug has returned! We are fortunate here yet the rest of the world still has a ways to go even as we in Canada move to what health officials are calling the endemic phase.

While governments and health authorities have planned out the gradual reopening of all aspects of our society the hardest phase is only beginning, the personal re-opening. Everyone will re-engage with society at their own pace. Comfort levels when it comes to social interaction, and in person services will be highly varied. We have all been through a form of trauma in the last months, in different ways and degrees. Virtual services will continue to be needed and those of us eager to open up again will need to adopt a healthy dose of mindfulness and respect. People with a variety of physical and cognitive disabilities have been impacted in unique ways by pandemic restrictions. A recent survey by the Canadian National Institute for the Blind captured the experiences of some people living with vision loss. In person services have been disrupted, home visits beyond those most essential stopped, social groups transformed and even the freedom to explore your own local community all become virtual, shut down or a mental risk analysis. Benches and seats disappeared and congregating spaces like malls and community centres closed or became restricted to essential business. The result; alongside keeping people safe from the virus, has been complemented by considerable isolation that itself comes with a unique set of health hazards both mental and physical. On the flip side some services have become more accessible. At least to those comfortable with technology. Social groups have moved online from virtual travel meet-ups to guitar lessons and knitting circles. Working remote become the norm for most previous office work with the aid of Zoom, Teams and other technologies that helped push business and society into functional online collaboration. This can create more opportunities for people with limited mobility to engage socially and in the working world. Now, anyone who has been working from home in front of a screen since March 2020 can probably relat to eye strain, Zoom fatigue and for some a loss of social ties that come with going into an office. Consider now anyone with a visual limitation or blindness; that duration and intensity becomes a burden. Federal support programs to people with disabilities; alongside seniors, have also been very limited over the pandemic. This has left many in more financially precarious positions than they were before the pandemic. Thus their means to engage with re-openings may be more limited than those who may have been had access income support or even been able to save more with reduced travel, work or activity costs. This is certainly not to say anyone has it most difficult; they have lived this experience in different ways and find themselves at the re-opening on different footings. Small business owners for example have navigated considerable uncertainty and may now hold alarming levels of debt, face different but no less challenging realities. As society continues to re-open let’s all be mindful of the need to be patient, bringing everyone along who may not have the same, means, abilities or experience while respecting their personal pace. The pandemic has introduced some ways of collaborating that enable people with disabilities, such as more work remote options, collaboration technology and e-services. At the same time the human touch is critical to people who may normally live with more isolation, who may have less ability to use technology or just need to find that balance between our real and virtual world. If you would like further reading on accessibility during COVID-19 and ways to make communities more accessible with recovery programs check out these resources:

At the time of writing this post the word is now six months in to a truly transformative global event with COVID-19. Large portions of society have moved to working from home while others navigate changing work environments to manage the risk of being exposed to a contagious virus. We behave differently in grocery stores, public transit and even on the sidewalk. As we dodge people to socially distance on crowded sidewalks, squint a little harder at a monitor for hours while working from home everyone is adapting around new barriers to living everyday life. In many ways the pandemic has been a great unifier around accessibility as everyone experiences different barriers to their mobility or freedoms. Lockdowns, health restrictions, social / physical distancing and the use of face masks are changing how we interact as a society. Our newly forming habits combined with how we spend time are also starting a wider conversation around how we use public spaces both indoors and outdoors. With the closure of many indoor spaces and more people working at home our streets, parks and public spaces have become prized real estate! Our provincial and national parks are increasingly seen as welcome escapes from cites not designed for social distancing. That is putting pressure on rural communities with people coming to their communities. Tiny condos or apartments once seen as resting space when not out socializing now become true homes and havens. On the positive side this is getting more people interested in the importance of park spaces, wider streets for mobility, and other amenities and places where we can safely spend time. Cities across the country are making short term adaptations to accommodate the reallocation of space on streets to accommodate pop up spaces, patios and more. A recent guide outlines many examples and references for other cities to follow. At the same time some innovations are putting up barriers to people with low vision and limiting equitable participation from people from all walks of society. Rules around social distancing can be challenging for someone with low vision or blindness who relies more on touch and physical contact to understand the world around them. Their ability to access public transit becomes more daunting both from fear of the virus and as service frequency is reduced in response to low ridership. Drive in only concerts and movies enable the show to go on but only for those who come with a required drivers license or access to vehicles. As we move from the immediate health crisis to a managed opening of our economy that will be with us until a vaccine is available it will be important that health guidelines enable inclusive participation while balancing public health objective for the population as a whole. This is even more essential as we learn how COVID-19 has impacted lower income and less mobile groups in our society. Consider for a moment the priority given by governments to the re-opening of boat launches and golf courses against public parks, libraries and playgrounds. So what can we do to keep the conversation going in support of a transformation that supports more accessible and inclusive spaces for everyone during and coming out of this pandemic?

Managing Eye Strain For anyone working from time over the past few months you have probably felt growing pressures on your eyes. Whether using a monitor, tablet or smart phone most of us have seen a doubling or tripling in our respective screen time in our work hours alone. Screen time outside of work hours only adds to this demand. Combined this places more demand on our eyes and mental concentration with strain accumulating over time.

Below are some suggestions on how people can reduce and manage eyestrain.

Just over a month ago now Ottawa was introduced to a much anticipated transformation to transit. The new O-Train Confederation Line otherwise known as the LRT (light rail transit) is Ottawa’s first substantive introduction to rail based transit since the initial start of the smaller Trillium Line back in 2001. The 12.5km line is the first phase of a much larger plan implemented by Ottawa’s transit provider OC Transpo. All along the route trains are separated from traffic traveling at grade, below ground and above ground. This new line has had a few challenges getting up and running which are not uncommon to major transit projects. Delays during construction pushed the opening date back by nearly 18 months and the transition from buses to trains has lead to some crowding and disruption to routine. Some time will be needed for both the system and passengers to adapt. Along with being transformative this new line brought forward an opportunity to introduce more accessibility to the transit system and surrounding area. This line should be encourage to spur more connectivity between stations and surrounding buildings, parks, services and other amenities while adopting accessible design features that improve mobility throughout the city. Phase 2 of the O-Train expansion is already underway. This will include extensions of both the Confederation and Trillium Lines. A refresh to the older Trillium Line should hopefully see many of the accessibility design features adopted for the Confederation Line applied during the redevelopment. Below I provide a quick run-down of my observations on how the new system performs. Overall my assessment is that the system has been built with good attention to accessibility. There are some areas for improvement however most of these could be remedied with minimal costs.

A special word about Blair Station. This station gets a special comment as it is the only station on the new line that still makes use of the infrastructure left over from the former Transitway station. Passengers traveling from the new Blair O-train station to the Gloucester shopping centre or adjacent bus station must travel up an over the bus corridor. On one end the new station has multiple elevators and modern staircase (no escalators). At the other end passengers descend through the former bus Transitway station that includes one small elevator and steep stairs. This represents a safety and accessibility concern given the volume of people who funnel through this corridor. The small elevator is also frequently out of service meaning that people needing elevator access must be shuttled across the road by bus! This station in particular will need some attention in the near future for improvement.

Have you ever passed through a courtyard, walked down a street, observed the interaction of people with a space and thought to yourself: whoever designed this almost got it right? When it comes to accessible design even spaces that have resulted from conscious thought about their design could do better to improve ease of mobility of people in the space. I have been in many spaces that are missing or have an incomplete element of accessible design. The spaces where we live, work and play often cut corners when it comes to complete design. This is not usually done on purpose, but is a result of infrastructure upgrades or a lack of a strategic vision for a space that includes accessibility. Oversight over the bigger picture of a space is needed to ensure everything comes together rather than a building by building or site by site implementation. We tend to cut corners to complete accessible design in several ways. Each of these has unique implications and solutions. Incomplete path of travel - Good design should consider where people start and end their journey, either in its entirety or just within a space. Failing to consider the full path of travel can result in segments of a journey that include many aspects of good accessible design but in bits and pieces. The user then does not have a consistent path to follow Common examples are intersections that have audible signals, ramps and countdown clocks only at some points, and none at others. Possible Solutions

Inconsistent application of design features - In this situation the Path of Travel is complete between the origin and destination for a user containing accessibility features all along the journey however there is an inconsistent implementation of the features throughout. Possible Solutions

Policy conflicts - Our urban spaces are shaped by many policies mostly developed at the municipal level with input from the public. These policies can sometimes present competing objectives that play out in how a space is constructed. Examples may include tree conservation policies that limit the widening of sidewalks or permitting policies that allow expansion of patios or other private uses into public space. The weak enforcement of by-laws or policies can also play a role here. Possible Solutions

Spatial hierarchy - Every space has a hierarchy of uses and users. Uses could include residential, commercial, recreation. Users can be defined in may ways from a specific demographic to their forms of mobility. This later point is a key consideration in achieving an accessible and welcoming space. Users can be pedestrians, cyclists, transit riders or motorists. The latter three modes ultimately become pedestrians when a particular space becomes their destination. Assessing the priority of these forms of mobility will fundamentally inform the design of the space and subsequently the comfort in mobility of other users. If the movement of automobiles is the priority in a space then it is unlikely to ever be a truly accessible space to people.

Possible Solutions

|

Devin CausleyTrained in town planning, an avid traveler and legally blind myself I write on issues and opportunities is see along my travels that could improve our cities from a visual perspective. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

|

|

Visually Accessible Cities is the creation of Devin Causley, a town planner by training who has also lived with low vision since birth. This unique combination along with insights from extensive travels around the world provide perspective on how cities can be built better to engage those of us with limited or no sight. Cities that are more visually accessible will ultimately be more livable for everyone.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed