What are the elements of accessible design?

The design of our cities is shaped by the perspective of professionals, the public and our elected decision makers. Guiding policy at the provincial / territorial and municipal government level determines how are cities are formed. Design for accessibility is specifically regulated at the provincial / territorial level however the degree of regulation varies across the country. Formal building codes and standards provide some guidance in combination with voluntary design standards. For more information about urban design and community planning visit some of the following organizations.

The earliest work on accessible design can be found in Selwyn Goldsmith’s 1963 publication, Designing for the Disabled. Community design has changed as a result of his work, most evident in the introduction of the cut curb. More work remains to be done. According to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) “accessibility is best represented when features are ‘built in’ as an integral part of the design and development process. Unfortunately, much of the time accessibility is an afterthought and features need to be ‘retro-fitted’ or adapted to ensure compliance.” Below are some of the key pieces the come together to support a well designed and accessible space.

The earliest work on accessible design can be found in Selwyn Goldsmith’s 1963 publication, Designing for the Disabled. Community design has changed as a result of his work, most evident in the introduction of the cut curb. More work remains to be done. According to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) “accessibility is best represented when features are ‘built in’ as an integral part of the design and development process. Unfortunately, much of the time accessibility is an afterthought and features need to be ‘retro-fitted’ or adapted to ensure compliance.” Below are some of the key pieces the come together to support a well designed and accessible space.

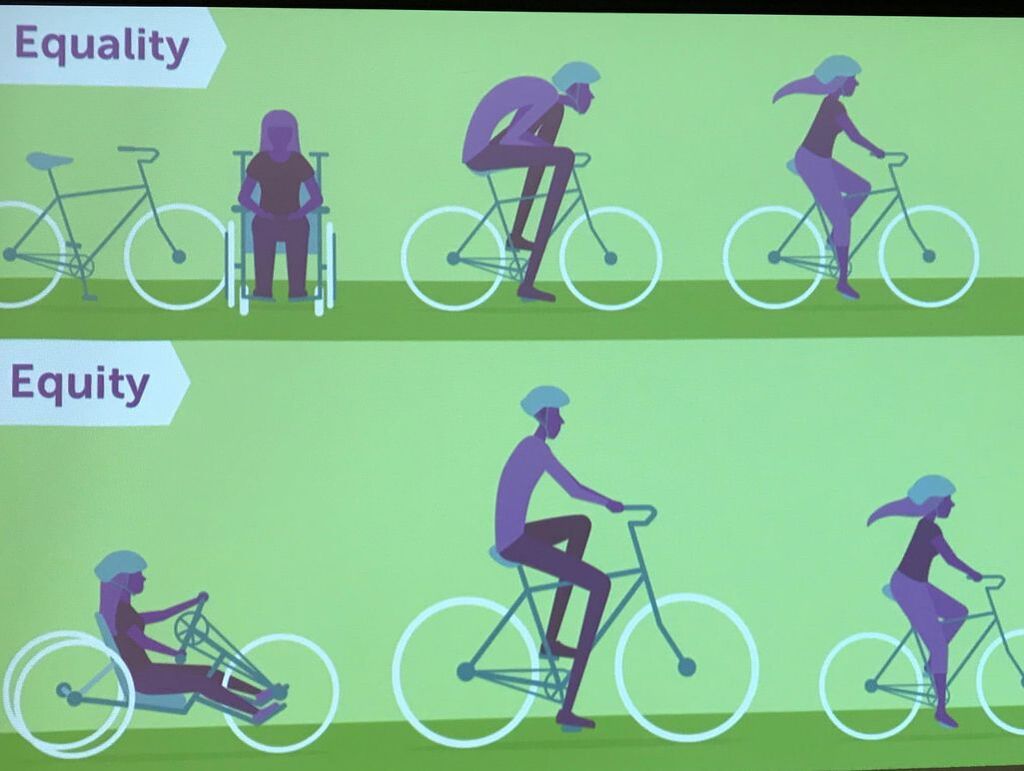

Diversity Lens

|

Before design or policy can start a sound knowledge of who the users are is critical. Knowing their abilities, limits and interests will inform the next steps. The services, features and infrastructure should be provide options to meet diverse needs and abilities. Exact needs will depend on local analysis, gathering data, speaking with local service organizations and consulting the public. Consider potential barriers associated with physical and mental ability, age, gender, income or culture.

In developing designs and policies consider how consultation and public engagement strategies themselves will be inclusive and barrier free. This will involve some understanding of the local community. Consider using a range of consultation techniques that may include virtual and in person meetings. When hosting an in person consultation such as a focus group or town hall ensure the venue is barrier free, reachable with a variety of transportation options and offers services to people on site to accommodate their needs This could include large print handouts of presentations. Another often overlooked barrier to inclusive public participation is when meetings are scheduled. Consider work and transportation schedules and child care needs of the participants. |

Wayfinding System - Maps, Guides, Signage

|

One easy way to improve accessibility is to provide easy-to-read information on directions and locations at regular points around the community. Information signs must be clear, use high contrast colours such as white on black or black on white, be presented in large, clear font and, whenever possible, be positioned at eye level. Street signs should be located on more than one corner of major intersections.

Proper signage has many complementary benefits beyond improving visual accessibility. Maps and directions enable tourists to find points of interest in the community, or shoppers to locate local vendors that they might otherwise miss. Think of your community like a shopping centre and how you can best connect people with services. The use of clear maps, highlighting points of interest, along with the reader’s current position, is also useful. Maps should use large fonts and not be cluttered with too much information. When put together this combination of maps and signage is known as wayfinding. |

Colours and Textures

|

Sidewalks are more than just somewhere to put your feet. They can be used to facilitate navigation. Engraving street names at crossings presents this information at an easy-to-read distance, especially when positioned at all corners. Texturing and high contrast colours can also be used to denote crossings, intersections, stairs or changes in elevation.

The use of paving tiles and street furniture also creates a safer sense of place for visual accessibility by providing landmarks as well as a sense of separation from vehicles or cyclists. Painted signs applied to the pavement, for example, can be used to denote shared pathways with cyclists. |

Separation of Space

|

Urban design in general benefits when a proper sense of place is created. Whether a person feels safe in the environment is highly influenced by a sense of separation from vehicles, bicycles, rollerbladers and other activities that are often traveling at higher speeds.

Space can be separated using a variety of low cost design features. Bollards, posts or rails are one option to provide either a permanent or permeable separation. Even occasional bollards along a street or at a corner can provide a sense of comfortable separation in a busy environment. Plus they offer somewhere to rest your drink or bag for a moment! The use of plain colours or textures is another option. This is quite common in the identification of cycling lanes and tram lines traveling at grade. Be sure to select high contrast colours. While it is important that colour choice blend in with the surrounding context it must be noticeable - even to those who may be colour blind. |

Policies and Enforcement

|

A good design alone will not ensure accessibility. That design must be supported by appropriate policies such as maintenance and servicing standards to ensure the infrastructure is in appropriate working order or high level policies that ensure accessible features are applied across a community, not just in isolated spaces.

Enforcement of regulations such as bylaws and permits will also be critical. This will include controls around parking of vehicles, loading bays and constructions practices that impact the public. With the rise of dockless bike or scooter shares the clutter created by these on sidewalks creates an increased hazard for people with mobility limits. They also create a general eyesore. Proper parking practices by users is key to removing barriers along with clean up by the system operators. |

Seasonally Adaptive

|

Seasons change and with them their unique qualities influence how we move around and interact. In some places seasonal variability is more extreme. Summers may come with extreme heat, drought and related impacts like urban heat island where a high presence of paved surfaces further increases local temperature. Winters may come with high snowfall, accumulating mounds of snow, ice formation and buildup of treatments like salt, sand and grit. Anything that accumulates can create an unexpected barrier to accessibility.

Thinking about the changing seasons and how they influence accessibility can inform ways that our designs need to adapt though the year. Consider how maintenance requirements will need to change, how seasonal impacts from snow and ice will be managed to avoid the creating barriers on ramps at street crossings or forming pools of water once melt begins to occur. Extreme heat or cold will also impact automated systems such as doors and audio systems if speakers become blocked. |

WayfindingMoving people through public space is the essence of wayfinding. As our cities and communities become increasingly urbanized with more people and economic activity we as planners need to become better at connecting people with points of interest in their environment. For further information on the principles of wayfinding I recommend reading The Wayfinding Handbook by David Gibson.

|

|