|

Last month I had the opportunity to speak about visually accessible cities to an audience of municipal elected officials at the High Ground for All Forum hosted by the Centre for Civic Governance. This was my first time presenting the subject to an audience of elected representatives. The session was delivered in collaboration with Amy Lubik from the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) who introduced the broader subject of social inclusion / exclusion. People facing accessibility barriers often face broader challenges of social inclusion so we found the topics to be very complementary and helped to open up the subject to a wider audience. Like most conference sessions we each opened the 1.15 hour session with concise presentations to introduce the topic, challenges and opportunities for civic leaders to respond. More importantly the presentations were followed by an interactive table top exercise intended to take participants on a virtual walk. This was my first attempt in moving the topic of visual accessibility into an interactive format. I thought I would share a bit about that workshop exercise in particular as it proved to be a valuable tool. Walking at Tables Thirty minutes were allotted for the table top exercise. First up was to divide the room into table groups: two tables with 12 people per table along with Amy and I as facilitators. Table participants were provided with a handout detailing the three stage virtual walk and some prepared descriptions of characters who could face different accessibility or inclusion barriers. Readers can find a copy of the handout attached to this post. Along with the virtual walk and character description, table facilitators had at their disposal a set of 16 large cards with photos of an accessibility barrier or good practice along with a laminated print map from a real city illustrating the fictitious walking route. Both tools enabled the facilitator to illustrate the experience. Participants reacted positively to the virtual walk! Each section of the walk provided a description of the surrounding along with possible barriers for each of the characters. Flash cards with photos of barriers matching the description along with some examples of good practices were introduced. Examples revealed real life experiences from their own communities that enabled people spoke to barriers in their own communities. In several cases people spoke to ways they had actively engaged with a group of people like those with mobility limitations or the elderly to test their experience in navigating their city. Throughout the discussion policy solutions were explored to obstacles encountered along the walk. In particular participants observed the policy conflicts, lack of enforcement and permitting issues that were contributing to the accessibility obstacles. Where to Next? Urban design and accessibility are both issues that are best appreciated through interaction and experience. Bringing people out into a real world situation will provide the riches experience however that is not always possible. Interactive exercises, games and tools to create the experience through visual aids and guides can be a practical alternative. Expect to hear more about interactive tools to advance visually accessible cities!

1 Comment

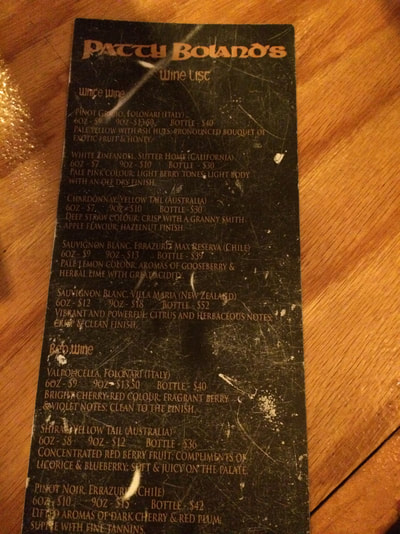

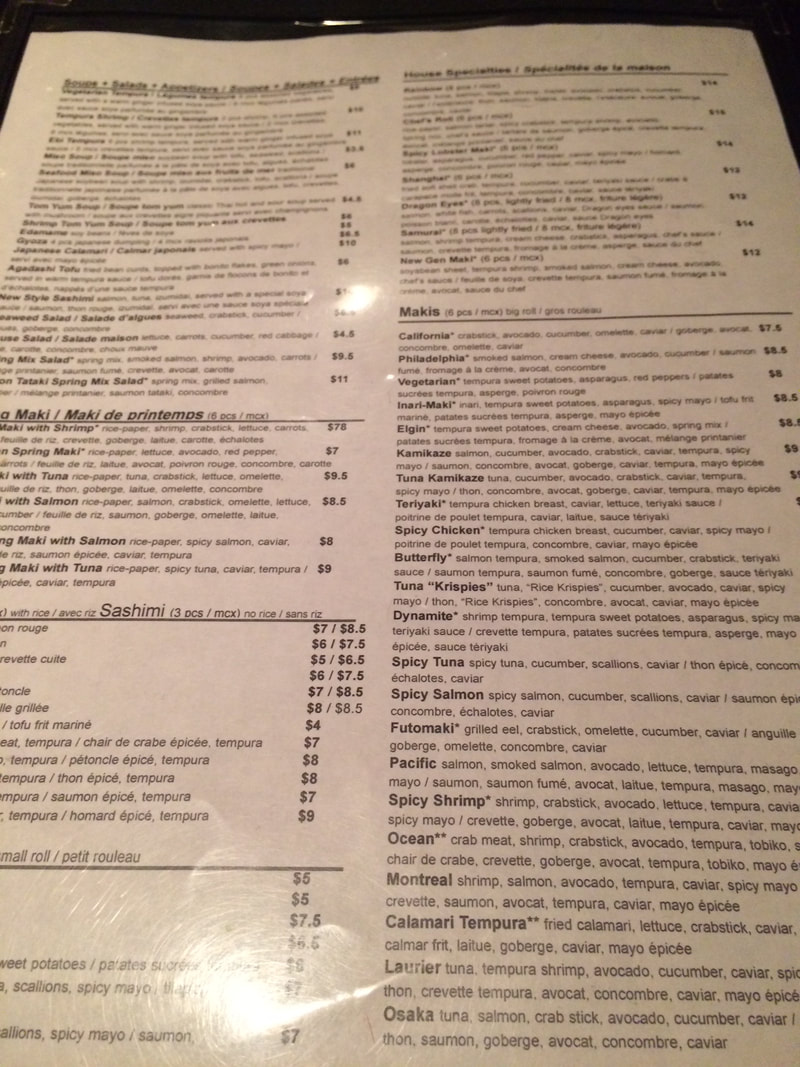

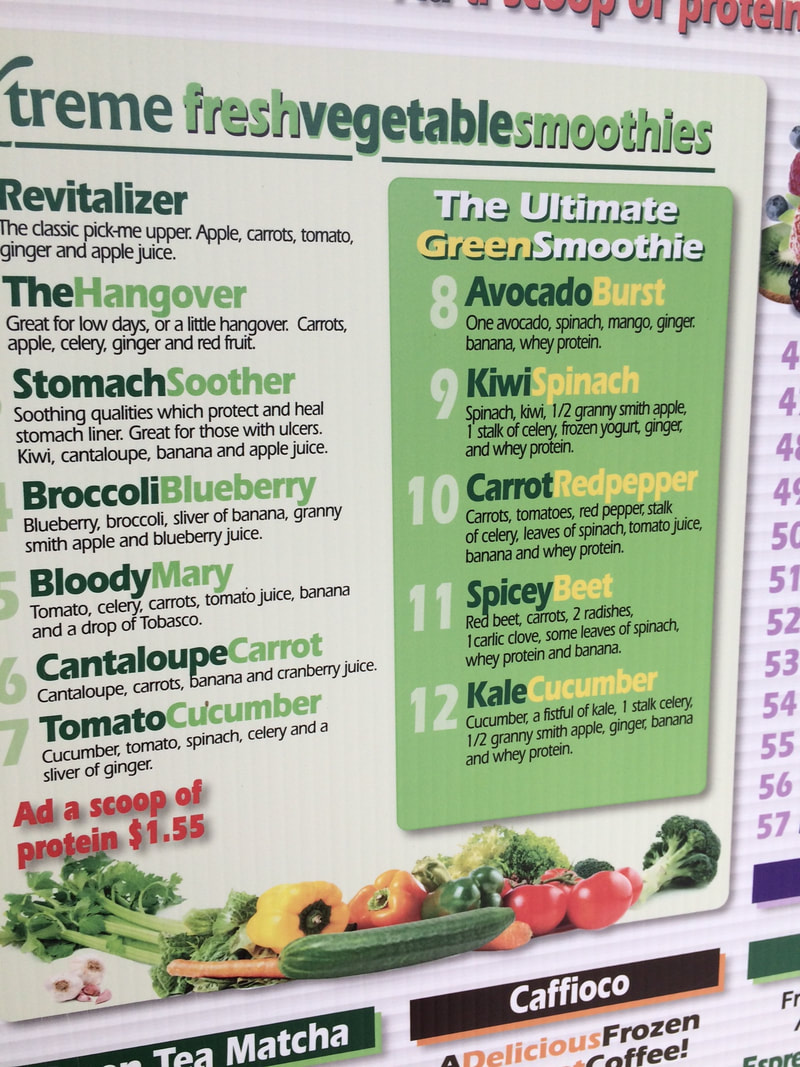

Picture yourself sitting in a restaurant. The waiter or waitress hands you a menu.. They point to the specials that are written on a board hanging on a wall at the far side of the restaurant. You start trying to read the menu, squinting ever tighter at the small, scripted font, placed on a poorly contrasting background. The menu has weird pictures and stripes of colour in the background, hampering your view. Add some dim lighting for mood. And now the server is back, waiting for you to order, when you have little idea about what is on offer. Why are they making it so difficult? Now for almost anyone this situation seems problematic and all too common place. Layer on a visual limitation and you have a very frustrating situation and unhelpful environment that can quickly translate into lost business for the restaurant. That is the situation with hand held menus, what about those ubiquitous hanging menus? The kind you find at fast food restaurants. Suspended behind the counter at a distance, usually in small fonts, shrinking ever more to accommodate pictures. Are you relating to any of these experience? Luckily there are solutions. The first is easy, design for the reader. Understand that these are communication tools first and works of art second. Choose appropriate font styles, sizes and contrasts:

Solutions

A Few Words About Etiquette In many instances that best way to assist someone in need of visual accommodation is a personal touch. Here are a few points for servers, owners or just friends and companions on when and how to offer assistance:

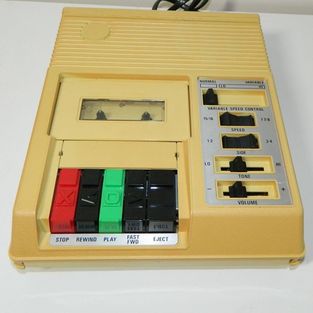

A four track cassette player used to play audio books recorded for use by people with vision loss now appears a relic of the past. A four track cassette player used to play audio books recorded for use by people with vision loss now appears a relic of the past. The world has changed considerably over the past two decades when it comes to visual accessibility. The introduction of the internet, smart phones and computers alone have radically boosted mainstream tools that aid in making our everyday environment accessible for all. In considering my own experience in coping with low vision I observe that I had the unique perspective of experiencing two eras of how the world approaches visual accessibility - the analogue and the digital. The analogue of accessibility came before computers and internet. It involved carbon copy paper and helpful classmates for schoolwork, dome magnifiers and closed circuit televisions for reading, binoculars to read distant signs, personal assistants for navigation, while audio books came on special cassettes produced by volunteers at dedicated libraries. Efforts to standardize colors, signage and identifiers were only just beginning while actions to improve accessible surfaces with ramps or domes had not even reached Canada. In general, this era was heavily reliant on the support of others to enable daily life of someone needing visual assistance. Many of these tools continue to exist in the new digital world however they are now complemented by advancements in technology. Now it is not just that there is new technology, clever people have been inventing solutions to help people with accessibility needs for over a century. A key difference is that most of the newer inventions benefit broader society along with those that assist people requiring visual assistance. Many of these technologies also connect or communicate with each other versus serving only a single purpose. Today the utility of a smart phone in your pocket and the many applications that have been developed as companions integrate tools that support accessibility. Smart phone applications that might have once taken a full size computer or team of people now provide ready to use OCR scanning and character recognition for reading of books or labels, photographic recognition of objects, navigation aids, audio guides and many more. They integrate cameras for use in reading or magnification of signs along with the general comfort that human assistance is only a call away without the hassle of finding a pay phone. Digital content including audio books or e-books is now produced on mass meaning that people with low vision have more content available and accessible on demand. A smart phone of course is only one simple example. Consider now what this means for developing visually accessible cities. Navigation is Getting Easier! When I first began exploring my city and later traveling abroad technology was very limited. I navigated with a paper map, spent a lot time searching for street signs, reading tiny print in guidebooks and hoped that the bus actually followed the paper schedule I had in hand! Today I have a digital guidebook in my pocket that can be magnified to any size that I need. Google has mapped the world’s streets and transit systems have real time information on most of that map. Infrastructure can Respond to Users Cities are rapidly becoming smarter, integrating technologies that instantly share information about people or functions of the city – how many cars are moving down a street or crossing signals timed according to rush hour periods. Similarly technologies can be applied to improve accessibility. Designer Ross Atkin provides some examples of how responsive street furniture shifts a smart city to become a clever city enabling people to experience their environment. The digital era now sees cities blending their fixed infrastructure and digital solutions alongside human support services. None of these three can meet the full need of providing a visually accessible city on its own nor can any of them be eliminated. Our infrastructure needs to be adapted with standardized signs, fonts, curb cuts, textures and colors. Digital technologies need to be employed that can provide descriptive texts of key landmarks and wayfinding solutions integrated with the fixed infrastructure. Human support services will remain critical. Organizations like the CNIB and others dedicated to providing support for those with accessibility are needed to provide services, and raise awareness. More Integration and Less Segregation The transition from an analogue to digital era is not only a change in technology but has been, and will continue to be, a change in mindset. It is a process of mainstreaming accessibility and those in need of accommodation. Providing custom supports and accommodation where needed yet whenever possible adapting the everyday to include people with an accessible need. Technology has helped this process alongside the efforts of many advocates who worked for decades to encourage the inclusion of people with accessible needs into contemporary classrooms and workplaces. Technologies Come with Strain Now you would think this era of instant information, digital interfaces and smart technologies would be an overwhelmingly positive change however it does come with negative impacts. The most obvious to the general public can be to the wallet. These new devices and the services to support them such as cellular data, internet and other service packages come with a price tag. Concurrently those in most need of these assistive technologies are lower income and thus may find their cost a barrier to access. Our digital ear is probably best defined by the abundance of screens that we now face every day. Computer monitors, televisions, smart phones, even crossing signals. Society now spends a considerable amount of time staring into the bring lights of these devices for long periods of time. This behavior amplifies eye strain. For someone already experiencing vision loss or impairment this can lead to faster eye fatigue, general strain or other discomfort. Researchers and technology developers should continue to look at ways to ease eye strain from our digital devices. A time of rapid change: for accessibility and for our cities. The last ten years alone have seen an explosion of digital solutions helping people meet their visual needs in reading, navigation and recognition. Infrastructure is being adapted and in many cases connected to the digital solutions in our pocket. Coordination should be encouraged between public and private interests to ensure opportunities to connect smart, accessible solutions with everyday infrastructure are made broadly enabling out cities to evolve. With such a rapid pace of change it will be imperative that the traditional support services for people with accessible needs continue to have the resources to assist people in need with these technologies. Teachers, employers and support organizations need to know about new technologies, applications and services. A digital era is only useful if people know what it offers and how to make use of what is available.  Mechanical dragon from La Machine at Ottawa City hall for public viewing. Mechanical dragon from La Machine at Ottawa City hall for public viewing. Summer is gradually turning into fall. Kids are heading back to school and everyone is planning for the colder months ahead. We take with us memories of fun summer times in the sun! Many of these times include attending in festivals, concerts and other forms of public entertainment or exhibition. Living in Canada’s capital, Ottawa, I am fortunate to be in the home of a host of amazing festivals and urban experiences. These were even more plentiful this year as Canada celebrates its 150th birthday! These events share many characteristics with those held in communities around the globe: they attract big crowds, accommodate people on a first come first serve basis (unless you have a handy VIP ticket for a price) and are generally very visual experiences. But do the organizers behind these fabulous experiences consider the diverse needs of the audience including visual accessibility? Is consideration given for a combination of accessibility features like platforms throughout, options for priority access to the experience, level surface, appropriate signage (or audio alternatives)? Let’s consider a few examples. This summer Ottawa had the benefit of hosting La Machine, an urban animation experience where a giant spider and fire breathing dragon roam the streets over several days stopping at various points for combat scenes with musical backdrops. The scenes were quite impressive and drew crowds in the tens of thousands. Let’s look at this first of its kind event in North America from the perspective of visual accessibility. Since the animated machines are quite large and travel along numerous routes along the city there are plenty of opportunities to get at the front edge of the crowd for a good view or get up close while they are at rest and on display in the evening. When it comes to the performance scenes however the common challenge of finding space close enough to see with low vision becomes a challenge. Get there early, elbow your way through the crowd or hope for some accommodation from fellow audience members are your main options. In some cases, elevated platforms are provided to accommodate wheelchairs however these are located far to the rear of the crowd. Instead, could a more equitable experience be provided by spreading these accessible spaces around the venue, allowing for improved viewing by anyone requiring accommodation? Next let’s consider the variety of outdoor concerts. I will make a quick distinction between public concerts such as Canada Day celebrations where government has more opportunity to intervene for accessibility and private concerts or festivals that have an admission price.. Both types of festivals have the three common characteristics noted above (crowds, priority, visual experience) Public festivals are generally available free of charge and often organized by government or community associations. Public funding is provided that carries with a greater accountability to taxpayers. Canada Day celebrations or other national holiday events, outdoor theatre in the park are good examples. There is typically a greater opportunity and even in some situation more regulated requirement to consider accessibility as part of the festival operations. In many cases these types of festivals tend to be located on public grounds, already more accessible with level surfaces, public services such as washroom and connection to public transit. Private festivals are generally those associated with a ticket purchase or entry fee and organized by private business and not-for-profit associations. Music festivals and food festivals are common examples. Well-run private festivals can feature many of the benefits of public festivals however accessibility considerations are more discretionary. Venues can often be much more crowded, lack fixed accessible infrastructure (i.e. ramps and accessible washrooms) and are often not on major transit lines. Ottawa’s Blues Festival and City Folk Festival are two examples for consideration. They are urban festivals, held on public lands within the city where level surface is available, signage is well done, accessible infrastructure services are available and they are served but public transit. Concurrently, crowd management has been an issue at times and no priority access to performances for visual limitations is provided. Wheelchair platforms are again usually placed at the back of venues. Lastly I will describe Mosaicanada, an outdoor garden sculpture park built for the bi-centennial celebrations. This is a more mellow experience, free to access and taking place throughout the summer allowing ample time to plan a visit suited to ability and crowd levels. Since the garden was built in an already existing park it already had in place paved and packed grit footpaths and central access to public transit. Sculptures were generally quite large with descriptive plaques. Print on these panels was of decent size but could have been improved with better contrast. While they provided description in English and French, Braille was not available. An audio guide however had been developed for the exhibition and free, daily guided tours were provided. Overall I feel this exhibition did well in providing options and design features to accommodate accessibility. Festivals and public events are a critical component to vibrant cities and community participation. These events engage all aspects of the community and thus need to be accessible and adapted to the needs of those diverse communities. Making these experiences accessible to those will low vision or other accessibility need can only serve to improve the experience for the general public. Accessible design is mostly a consideration of more affluent or developed countries. Indeed most of the examples used on this site pull from design or technology solutions being applied in Canada, Australia, United States, Europe and a few of the larger cities across Asia. These countries along with their regions and local authorities have the benefit of building upon an established culture of planning, regulation and notion of equity in access to services. When you begin to venture outside of these countries the story begins to change. How does a person with low vision or blindness cope in a potentially less planned or controlled environment? A few months ago I had the opportunity to spend a few weeks traveling through Vietnam, a country full of rich history, friendly people and amazing food! It also has plenty of scooters, few traffic signals, limited signage and the organic flow to cities that is common to developing countries. There is an electric combination of excitement and chaos to watching the flow of traffic through the streets. Scooters are the dominant form of transportation filling both the streets and sidewalks.... where sidewalks even exist. Walking through the streets can be an adventure. A person with full sight will find this experience intimidating, possibly frustrating and even maybe exciting as there is a logic to the flow once you learn the norms of the road: walk slowly, purposely forward and the traffic will flow around you. As someone with low vision but functional sight this environment was manageable but quite fatiguing as the concentration to keep track of the constant intensity results in incredible eye strain. Navigating without sight entirely could be a whole other challenge. This left me with two questions: how do locals with low or no vision cope and how would a blind or low sighted person traveling from abroad adapt to this environment? Through my time in Vietnam I never encountered someone with a familiar white cane like we have in North America so it is hard to say exactly how the locals navigate. There are a few non-profit agencies in Vietnam who provide support to people with blindness so some resources are available to integrate them into society: at least in urban areas. I can only speculate that the type of day-to-day independence that is more readily available in developed countries is very different. Urban environments have limited supports for navigation while the outer suburbs are designed to be accessed by vehicle. Whether traveling from abroad or as a local, support from a companion is advised. That said there were signs of efforts being made to change the urban environment to include aspects of accessible design. This was more evident in the south than in the north. Saigon specifically is beginning to include textures, colours and ramps in new development. Connectivity is not complete so you may not be able to rely on the design environment along a full path of travel. Additionally, scooters still have full reign in their use of the road and sidewalk for parking. This presents a cultural challenge for the country to consider. In the coming years cities like Saigon and Hanoi will need to consider how to integrate the dominant forms of transportation with providing a welcoming urban environment that is safe and accessible. This post is about a few opportunities that are currently open to contribute your perspetive on what makes a visually accessible city.

Nominate an Accessible City for the Rick Hansen Foundation's Award The Rick Hansen Foundation is launching the Accessible Cities Award, a national award designed to recognize and celebrate municipalities, and the planners, developers, architects, and builders they work with, for creating accessible places for people with mobility, vision and hearing challenges. If you know of a city that is doing their part to become more accessible and inclusive, nominate them online to win the title of Canada's Most Accessible City by March 3, 2017. Federal Consultation on New Accessibility Legislation. The Government of Canada is currently consulting on new legislation to improve accessible services. This consultation is interested to hear from you about topics ranging from barriers in the built environment, to ways of changing attitudes or updating policies to advance accessibility. Consultation closes in February 2017.

Admittedly great examples of accessible design are much easier to find in warm weather climates. Snow and ice can quickly bury colours and textures in the sidewalk which are some of the simplest strategies to improve navigation. So what do you do to assist people in cold weather climates? Well there are certainly some solutions and some issues.

Proper snow clearing should be a priority. This may mean giving priority to certain paths of travel where low vision people are know to visit. Ensure that snow and ice are cleared back from corners, texturing and paints are in a good state of repair so that they stand out. Signal buttons at intersections should also be clear of snow and easy to access. Far too often snow is plowed up against the light standard making access to signaling devices (audible or otherwise) impossible as seem in one of the photos below! Winter is one instance where design may not be sufficient and some coordination with social services and transit systems may be required to help people navigate by other means. Enforcement of proper sidewalk clearing by area businesses and residents will also be critical. In any case making area streets clear and navigable is of benefit to everyone. |

Devin CausleyTrained in town planning, an avid traveler and legally blind myself I write on issues and opportunities is see along my travels that could improve our cities from a visual perspective. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

Visually Accessible Cities is the creation of Devin Causley, a town planner by training who has also lived with low vision since birth. This unique combination along with insights from extensive travels around the world provide perspective on how cities can be built better to engage those of us with limited or no sight. Cities that are more visually accessible will ultimately be more livable for everyone.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed